To Anneal - or not to Anneal

by Woodrow Carpenter

(First published in Glass on Metal, vol. 23 # 3, June 2004, reproduced with permission of the author)

At the Enamelist Society Conference in 2003, two enamellists had questions concerning annealing. One, with glass working experience prior to enamelling, was puzzled that annealing is not a requirement in enamelling. The second, who had no glass working experience prior to enamelling, that someone would think annealing could be of value in enamelling. They wanted to know why it is required in glass working and not in enamelling. The answer was: 'the metal keeps the glass in compression.' This caused many questions, which leads to this article.

First, why does the glass worker have to anneal? There are two primary reasons. The first is easy to understand with common everyday logic. The thermal conductivity of glass is relatively low. When the surface of a glass rod is heated, there is a sizable lag in time before the center of the rod reaches the same temperature. And by that time, the surface is even hotter. Since glass expands with temperature, it is obvious the surface is expanding faster than the center. This sets up a strain which is opposed by internal restoring forces called stresses. If the stress exceeds a certain limiting value, rupture will occur. When cooling, the surface cools and contracts faster than the center, setting up stresses and strains in a similar manner.

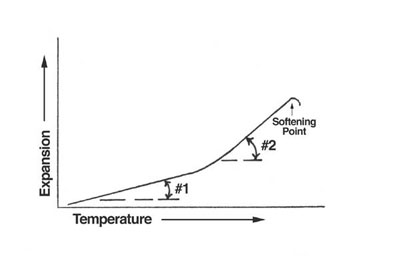

- Figure 1. Typical thermal expansion curve of glass

The second primary reason is not so obvious. Figure 1 shows the thermal expansion curve of a typical soda lime glass from room temperature to its softening point. The rate of expansion, #1, is relatively constant from room temperature to 900°F - 950°F, where it begins to rapidly increase its rate of expansion, #2. This is where the glass begins to change from the behavior of an elastic solid to that of a viscous liquid. This is known as the glass transformation temperature. Here, the molecular structure of the glass changes without the glass visibly changing. Our interest is the internal stresses which form as the glass cools from its softening point to room temperature.

More than 5000 years ago, practice showed that glass articles cooled directly from their working temperature to room temperature would usually crack or shatter. Practice also showed if the cooling glass was allowed to dwell at a certain point, and then gradually cooled to room temperature, it would not crack or shatter. We know now that certain point as the transformation area. The area where glass must remain in order to relieve stresses which may have formed while cooling to this stage as well as any stresses which may have formed because of the glass structure rearrangement while changing from a vitreous liquid to an elastic solid. Now the stress-free glass must be cooled slowly, because of the first primary reason given above in order to be stress-free at room temperature. Otherwise, it would crack or shatter.

- Figure 2. Typical thermal expansion curves of enamel and copper

Second, why do enamellers seldom anneal? Figure 2 shows the overall expansion of enamel is lower than that of copper. Enamel is selected with this basic requirement in mind. The rate of expansion of copper is linear throughout the normal enamelling temperature range. The enamel has two rates of expansion and a transformation zone similar to the glass worker's material. Point #1 in fig. 2 shows a small cross section of an enamelled copper article starting to cool. The enamel is a viscous liquid conforming to the metal surface. Neither the enamel, nor the metal places much stress on the other, even though they are contracting at different rates. At some point near the lower end of the enamel's transformation zone, due to the different rates of contraction, the enamel will be in slight tension, point 2, figure 2. This can be easily observed.

Apply a coat of enamel to one side of a 1"x 6" copper strip and fire, laying flat, on a sturdy flat firing fixture. When it comes out of the fire, the strip will be flat. Within 20 - 30 seconds, the ends will begin to raise. Point 2, figure 2, and photo #1. 45 - 60 seconds later, the ends will begin to lower, in about 60 seconds the strip will be flat again. Point 3, figure 2, and photo #2. Soon, the center begins to raise, giving the strip a convex bow, point 4, figure 2, and photo #3. The contraction of the metal has caught up with and exceeded the contraction of the enamel, removing the slight tension (bad) stress and replaced it with compression (good stress).The need for annealing has been removed and a needed stress applied. Otherwise, upon reheating, the metal's faster rate of expansion would put additional tension on the enamel, causing large cracks and sometimes large pieces to jump off.*

- photo 1

- photo 2

- photo 3

Photos 1-3 show a phenomenon which appears to be a basic requirement in enamelling- formation of slight tension changing to moderate compression. If both sides of the strip are coated with an equal amount of enamel, this phenomenon will not be visible as shown in photos 1-3. However, the stresses will still exist, this time divided equally between the two coats of enamel. Each time an enamel is fired and cooled, without annealing, these stresses will be present.

Third, are there times when enamelers should anneal? Yes, unfortunately at times problems do occur. Problems such as hair lines, healed-over cracks, open cracks, chippage and warpage (not caused by faulty support) are all signs that you could have considered annealing.

All are signs of some incompatibility of the design, metal, enamel, procedures, or something unsuspected. Often the problem is caused by a combination of two or more things. Of course, it is far better to correct the incompatible part of the process, if possible. However, most defects are after-the-fact and first seen as the piece is cooling. Now, the question is, how to save the piece? If the incompatibility is slight, perhaps refiring and annealing will save the piece. Remember, annealing is a nuisance and there are no guaranties.

How do I anneal? The most simple is to refire, shut off the furnace, and let the piece cool within the furnace. If there is a fear of over-firing, open the door slightly after shutting off the furnace, and close it again before the front of the piece gets below 1100-1200°F.

After the final fire, the piece can be transferred to a second furnace which is at 950°F. Hold this temperature for 30 minutes or more, turn it off, allowing the piece to cool within the furnace.

I remember one industrial piece which had to be placed into a furnace at room temperature, slowly heated to 950°F, transferred to a second furnace to be held for a period of time, and finally cooled to room temperature within the furnace. We ran this product day after day for years. The price was not cheap.

Continuous furnaces, used in industry, heat the ware slowly, then cool it slowly. Some ware fired in these furnaces have less defects than when fired in a batch-type furnace.

See the accompanying article for how Henry Bone, the most famous English enamel painter, solved his problems with hairlines and undulation.**

*Does this mean problems when refiring an enamel which has been annealed? Probably not, most kilns lose considerable temperature when an enamel is inserted and they are slow in climbing back to temperature. The kiln could be turned off a few seconds, several times during the heat-up, if a slower rate of heat-up seems appropriate. .

** This article is not reproduced on this site. Interested enamellers can find it in GoM. or ask a copy by email.